HOCKEY AND CANADIAN CULTURE

If you ask anyone in or outside Canada what makes that country different from other nations, it doesn’t usually take long for hockey to emerge as something that seems characteristically Canadian.

Canada’s greatest and most wide reaching export, hockey cannot be ignored in Canada, whether one appreciates the game or not. There are outdoor and indoor rinks in every community across the country; there is year-round media coverage of hockey; most Canadians alive at the time can tell you where they were when Paul Henderson scored the winning goal to beat Russia in the Canada/Soviet series; a hockey scene figures prominently on the back of the five-dollar bill; and, when asked in 2004 to come up with a list of the ten greatest Canadians of all time, millions of Canadians polled put both Wayne Gretzky and Don Cherry in the top 10. “Hockey,†writes novelist David Adams Richards, “is where we’ve gotten it right†(60).

But how does hockey connect to Canada today? How can an extremely multicultural country that has long considered itself as a peacekeeping nation still see itself reflected in one of only two sports (the other is lacrosse, Canada’s official national summer sport) in which fighting is an accepted and even lauded part of the game?

I. Origins

In his introduction to the tenth-anniversary edition of Hero of the Play, poet Richard Harrison discusses the origins of hockey. There has long been a debate over whether hockey first developed and was played in Windsor, Nova Scotia, Kingston, Ontario, or Montreal, Quebec. More recently, there appears to be strong evidence that hockey was played even earlier by sailors stranded in the Arctic as part of Franklin’s ill-fated expedition to discover the fabled Northwest Passage.

In Harrison’s eyes, though, “[w]hat’s important isn’t where the origins of hockey is found in Canada, but how Canada finds at least a part of its origin in hockey” (16). Indeed, although historians and hockey lovers debate where the first game make have taken place, no one questions the fact that the game develops Canada or, perhaps even that Canada develops out of the game. As Harrison puts it,

“Hockey emerges in the Canadian past at the time the Canada we lived in then as separate communities was being made into Canada we live in now as a people. In mythic terms, hockey is one of the few things that could be said to be ours from the beginning of Canadian time.

And for all its simplicity, like all creation myths, hockey is also about Canadian light and Canadian darkness. All creation myths have a place for the way their people experience not just the light and the dark of the seasons of the day, but the light and the darkness in themselves. Hockey’s simplicity and childish roots offer us the play that we love for its own sake; its skills and speed give us what we admire in those dedicated to excellence. Its violence gives us a view into our own.” (Harrison 16-17)

Hockey is, in writer Morley Callaghan’s words, “the game that makes a nation†just as much as it may be a game the nation made.

II. The Nation(al) Game

Naturally, there is a lot at stake in Canada’s claim to be the “first nation of hockey,†to quote the rant from “Joe Canadian†in the 2000 beer commercial from Molson’s “I Am Canadian†campaign. You’ll see the words “it’s our game†in everything from commercials for beer and Tim Hortons to school textbooks. The notion that hockey and Canada are equal parts of one another helps advertisers, the sport of hockey in Canada, and broadcasters trying to increase their audience numbers.

Â

There is plenty of evidence, of course, to suggest that not only was hockey Canada’s game at its outset but that it also remains that way today. One need only look at the fact that over 500,000 children, women, and men are registered each year in organized hockey in Canada. At the professional level, Canadians still make up over 50% of players in the NHL, more than two and a half times the number of American players in the league. What makes that number even more extraordinary is that Canada has only one-tenth the population of the USA.

Canada’s dominance in international competition over the years also supports this idea. While the men’s teams have won Olympic gold medals in 2002 and 2010, the women’s team has won gold in 2002, 2006, and 2010. The women’s team, along with that from the United States, have been so dominant in international play that there is pressure to have the sport removed from the Winter Olympics until players from other nations can catch up.

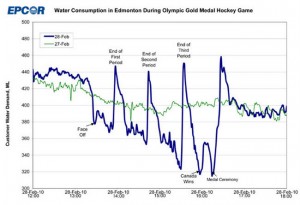

Television viewership of hockey in Canada also demonstrates Canada’s connection to the game. The 2010 Gold Medal game between the Men’s hockey teams from Canada and the United States was the most watched sports program in Canadian viewers, netting 13 million viewers at its peak. The following chart from the City of Edmonton’s water utility provides another way of demonstrating just how many people were watching the gold-medal game on February 28th.

Â

Regardless of how strong the connection of hockey to Canada might be, the increasingly aggressive assertions that hockey is “Canada’s game†and no one else’s naturally rubs other countries (and many, many Canadians) the wrong way. Such rhetoric, which one hears employed mostly by advertisers such as Molson, Coke, and Tim Hortons and by some commentators, most notably Don Cherry, seems counter to the modesty and humility for which Canada is known. Brash self-confidence seems, to many Canadians, to be “un-Canadian.â€

Â

Â

As Bruce Dowbiggin points out in his 2008 book The Meaning of Puck: How Hockey Explains Modern Canada, it is not a coincidence that the most revered hockey stars in Canada are the ones who are the most humble and, like Crosby and Gretzky before him, are quick to point to their teammates as the reason behind their individual success. Unlike the more individualistic culture of the United States, Canada and Canadians see themselves, for better or worse, as being more concerned with the success of the collective rather than the individual. As such, they can be quick to put in their place those who are deemed to think too much of their own accomplishments. Dowbiggin looks to an earlier book on hockey for an explanation of this tendency:

“Whatever the origins of Canada’s self-abasement, Peter Gzowski understood the syndrome in his 1982 book The Game of Our Lives. ‘We are not good with our heroes, we Canadians. Starved for figures of national interest, we, or our media, seek out anyone who shows a flicker of promise and shove them on to the nearest available pedestal. We leave them there for a while, and then we start to throw things at them'” (Dowbiggin 75-6).

III. National (Contra)diction

As Bruce Dowbiggin points out in The Meaning of Puck, one does not need to scratch far beneath the surface to see how Canada’s connection to hockey seems to reveal some strong contradictions about the country and the sport: “In its quick, brutal fashion, hockey is a perfect wedge in the emerging urban/suburban-rural split in Canada — the so-called Tim Hortons versus Starbucks. Hockey lovers regard urban Canadian culture as some extended episode of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, a fashion/design industry that keeps Canada out of wars and in designer jeans. If Canada were a TV program, it would be The Odd Couple. Hockey is Oscar, lounging in his underwear in his a fraying BarcaLounger. The rest of Canada is Felix, asking ask Oscar to pick up his pizza boxes, put on a clean shirt and take the empties back to the beer store” (21).

Although I would argue that Dowbiggin overstates this case – the lines between urban and rural Canadians are hardly as cut and dry as he proposes – it is important to remember that Canada is much larger than hockey; for all the Canadians obsessed with the game, there are just as many who focus on other parts of Canadian life, even if they do sometimes tune into the Stanley Cup Finals or the Olympic Gold Medal game. One of the most crucial differences of opinion among Canadians revolves around the role of fighting in hockey. Despite its well-deserved reputation in both World Wars as some of the fiercest troops on the battlefield, Canada has, over the last fifty years, become known around the world as a peacekeeping nation, a moderating force in international debate that sees war as the last and most unappealing option.

“How,†asks Dowbiggin, “does the nation that has (until the recent Afghan mission) cherished its image as an international peacekeeper reconcile its pacifism with the brutal, pitiless heart of hockey, its national sport?” (22). While some critics see the acceptance of fighting in hockey as an aberration that should be eliminated once and for all, others, like Don Cherry, see this as part of the “code†of hockey that is as much a part of the game as anything else. While he doesn’t openly come down on one side or the other, Harrison sees this issue as less of a contradiction than an indication of Canada’s complex relation with the game and its own history; Canada is a country that, at least among certain segments of its population, sees an importance in “smiling ugly.â€

Â

Â

Dear Mr. Martin,

my name is Nicolas Mayer I am from Beuren, Germany. The next Year I’m writing my A level and for that I must write a seminar work. In a group of 15 pupils we prepared some facts about whole Canada. After that we must decide about on special subject in and around Canada. Because I’m so intrested and fascinated in sports, I decided to write about icehockey in Canada. Although I have seen some NHL games and of course the Olympic Final 2010 in Vancouver, where the Canadian people showed how fascinating this sport can be. During my search in the internet I found your site and want to ask you, if you can send me some informations about Canadians feelings in hockey.

It would be awesome if you can help me.

The precise title for my work is: “Hockey in Canada – More than just a game.â€

Hello Mr. Martin!

My name is Caroline and I am from Sweden. I am writing an essay about Canadian Hockey, I found your website while i was searching for information. I was wondering if you also could send some information about how the Canadian people feels about the game and why it is such a big part of the Canadians life´s. How the Hockey belongs in their everyday life.

I would appreciate that !